Queen Elizabeth II and President Dwight D. Eisenhower officially opened the St Lawrence Seaway on June 26, 1959 in a dedication ceremony near the harbor of Montreal, Canada. After some speeches, the two leaders boarded the royal yacht Britannia and sailed through one of the seaway’s new locks.

According to on-site British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) reporting, people along the Britannia’s route cheered and waved flags. Church bells rang. Balloons and fireworks were released. Bands played. Whistles from ships in Montreal Harbor wailed. All the while, Queen Elizabeth and President Eisenhower stood chatting on board and serenely waving to the crowds.

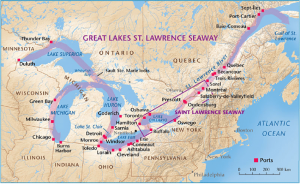

At the time, the 2,300-mile seaway was one of the largest civil engineering feats ever undertaken. Its goal was clear: create a modern commercial superhighway allowing large cargo ships to travel from the Atlantic to the Great Lakes and the heart of North America.

In the process, riverside communities were relocated, roads were built, bridges were raised, and canal locks were constructed and modernized. It took 22,000 workers five years to complete at a cost of almost $500,000, two-thirds of which was paid by Canada. The project used enough cement to build a highway 1,000 miles long and enough steel to girdle the Earth. It was a big deal.

The St Lawrence River had always been a natural highway for transportation and commerce. Early French colonists used it to transport beaver fur back to Europe. Yes, you heard correctly. Beaver fur was a prized commodity during the 17th and 18th centuries, for making hats. It was soft, pliable, and durable, and the hat-mad Europeans had practically decimated their beaver populations.

The French established a network of fur trading posts along the St Lawrence, the most important of which was Montreal, as far upriver as ships could travel back because of treacherous rapids. The fur trade grew so lucrative and the river so important it incited squabbles between the French and English for control over Canada and the Great Lakes region, which England won in what we Americans call the French and Indian War.

Now that the St Lawrence was on the map, enterprising men of politics, the military, and industry dreamed of connecting the big river and Great Lakes with its abundant resources to the Atlantic and overseas markets.

The problem they faced was that while the five Great Lakes form a single, naturally interconnected body of fresh water flowing to the St Lawrence River, no fully navigable route linked them all. A series of narrow, often shallow and rocky rivers and channels connecting the lakes were major impediments that had to be cleared out and enlarged.

The St Lawrence River itself posed many other challenges to navigation — fog, ice in the winter, strong tides, and multi-directional currents. And then there was Niagara Falls — the granddaddy of all obstacles — on the Niagara River that connected Lake Erie with Lake Ontario.

In 1824, Canada began work on a canal to bypass the Niagara waterfalls. It was called the Welland Canal, and European immigrants dug it using little more than picks and shovels. When completed nine years later, it ran 27.5 miles with a series of navigation locks lifting and lowering ships 326 feet (the height difference between Lakes Erie and Ontario) and competed with the Erie Canal for maritime commerce.

About the same time, Canadians began digging another canal to go around the treacherous rapids near Montreal. The two Canadian projects were instrumental in creating the first commercial waterway linking the great inland lakes to the St Lawrence River. Boats brought grain and iron ore from the west to Montreal where it was then transferred to ocean vessels.

Serious talks about enlarging and modernizing the entire water highway began between America and Canada in the early 20th century as larger ships

were now starting to render the patchwork waterway obsolete. World War I interrupted negotiations. President Roosevelt wanted these expansion projects included in his New Deal public works agenda during the Depression, but they were blocked by the strong U.S. railroad lobby and Eastern states with major seaports that feared competition. Politicians feared high construction costs.

Eisenhower finally broke the logjam in the 1950s. He had long viewed a modern St Lawrence waterway as critical to national defense and commerce, especially getting iron ore to supply steel production. Perhaps he remembered Nazi U-Boats attacking Allied ships in the Gulf of St Lawrence? In any case, the savvy former general pushed through legislation committing America to join its northern neighbor and build the St Lawrence Seaway.

Was it worth it? The U.S. Department of Transportation estimated in 2017 that maritime commerce on the Great Lakes St Lawrence Seaway System annually sustains 227,000 U.S. and Canadian jobs, and generates $35 billion in annual business revenues, $14 billion in annual wages and salaries, and $5 billion in federal, state, provincial and local taxes each year. Since 1959, more than 2.5 billion tons of cargo (estimated at $375 billion) have moved to and from Canada, the United States, and 50-plus nations.

This economic success story, however, comes with an asterisk that reminds us of the hubris in thinking we can control the environment completely without repercussions. Since 1959, more than 190 species from around the world have arrived via the waterway, making it the most invaded freshwater system in the world.

The Russian zebra mussel came as unintentional stowaways in the hulls of ships. The striped-shell mussels — with no natural predators — have been spreading like wildfire since first spotted in the 1980s. They’ve caused about $4 billion worth of damage to the watershed ecosystem and to the boats, locks, water intake pipes, and other infrastructure to which they tightly attach.

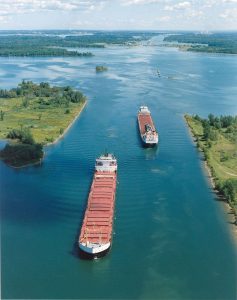

St Lawrence Seaway today remains a key commercial trade route, and the number of ships passing through it grows every year. Looking to the future, seaway authority officials want to digitize the seaway and make it a smart marine corridor. For example, they want to use artificial intelligence and automation calculate travel planning based on real time weather conditions, currents, water levels and navigational restrictions at various times of the day, and for different sized vessels. This kind of improved planning saves time and fuel and enables cargo to travel more quickly and efficiently.

Clearly, enterprising men and women are still dreaming about how to build a better St Lawrence Seaway. They’re just using computers now instead of picks and shovels.

See marinas on the St. Lawrence River here!