GROWING UP IN THE South, I remember my Grandma Missy describing the difference between Charleston and Savannah, two charming and competitive port cities I’d not yet had the privilege to visit. She explained to me that both were like the attractive daughters of a gentile Southern family. Older sister Charleston married well and joined the D.A.R. And Savannah? Well, the poor girl had an affinity for strong drinks and was a little cuckoo in the head. Bless her heart.

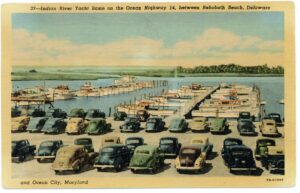

I think about that anecdote whenever I describe the difference between Lewes and Rehoboth, the two main municipalities dominating the 28-mile long Delaware seashore. They’re only eight miles apart geographically, but like Charleston and Savannah, they couldn’t be more different in temperament and history.

Quaint Lewes prides itself on its historic preservation and colonial and maritime past. Visitors today peruse its antique stores and museums and sup on the catch of the day in dockside restaurants. Independence Day features an annual parade of boats festooned with red, white and blue décor that winds its way down the Lewes-Rehoboth Canal to Fisherman’s Wharf.

Rehoboth, founded as a modest Methodist retreat, now draws a different congregation, a delightful and eclectic mix of highbrow and lowbrow, homo and hetero. Visitors enjoy au courant dining and outdoor drinking, pizza and French fry joints, art galleries and t-shirt shops, and a golden sand beach regularly rated one of the best in the mid-Atlantic region. Drag volleyball on Labor Day draws hundreds of spectators to the beach at the south end of the town’s wooden boardwalk to say goodbye to summer in a unique way.

Grandma Missy passed away 10 years ago. But even into her 90s, she enjoyed telling me the history of places, usually with a vodka martini in her hand. I invite you to grab your favorite libation, settle back and let me share stories about the unique history of these two Delaware towns.

Lewes: The First Town in the First State

Exploration & Colonization

In 1631, Dutch whale and fur were the first Europeans to settle in what is now the State of Delaware. They selected the geographically advantageous location where the Delaware Bay meets the Atlantic Ocean and named their settlement Zwaanendael. A tribe of local Native Americans wiped it out a year later.

The Dutch, however, were not easily deterred, and by 1673 another settlement known as Whorekill was built back on the cape and claimed by both the Netherlands and England. Should you think the name of the town a tad unsavory, well, you aren’t alone. “Kill” is Dutch for creek, and the settlement was indeed sited along a creek flowing into the bay.

“Whore,” on the other hand, has been interpreted two different ways. Some historians say the English corrupted it from the name Hoorn, a Dutch city where many early inhabitants came from. Others believe it was because prostitution was prevalent in the frontier settlement full of rough and tumble Dutch seamen, soldiers and fur traders. The Dutch word for a prostitute is “hoern.”

Either way, the English burned the town on Christmas Eve 1673 and soon took control of all Dutch land in North America. William Penn became the proprietor of the Pennsylvania colony, and he renamed the settlement at the cape Lewestown.

By the 18th century, Lewestown had grown slowly and steadily, and like many other smaller mid-Atlantic port towns, it was harassed and sacked by pirates. Despite remaining a hot bed of Tory sentiment, not much happened along coastal Delaware during the Revolutionary War. After independence, the three lower counties of Pennsylvania along the Delaware River organized as the separate state of Delaware and became the first state to ratify the Constitution.

War of 1812

Patriotism was on full display in Lewestown during the War of 1812. With Philadelphia at that time the most populous and economically important city in the country — and with the new DuPont gunpowder mills near Wilmington — the Delaware Bay was a critical asset the British sought desperately to control.

In March 1813, a flotilla of British ships arrived off Cape Henlopen and demanded food and water. When the request was rebuffed, the British bombarded the town. The outmanned citizens fought back. According to historians, town folk gathered enemy cannonballs and re-fired them, striking several ships and sending the flotilla scurrying to safety offshore. The battle was national news, and a volunteer militia of riverboat pilots successfully defended the bay for the duration of the war.

Eyes on the Atlantic during World War II

Lewes played another important role in the defense of the nation during WWII. The day after Pearl Harbor was attacked, the U.S. Coast Guard began constructing one of the most formidable, heavily armed coastal defense forts in the country. Fort Miles, perched atop the dunes at Cape Henlopen, cost $24 million and was designed with a series of gun installments powerful enough to fight the strongest ships in the German navy fleet.

Today, a museum in one of the underground bunkers brings to life stories of submarine warfare off the coast. Visitors can walk up comfortably to the top of a restored observation tower to see firsthand how soldiers used triangulation to track suspicious ships and submarines in the bay and ocean. The concrete used in the towers’ construction was made with beach sand and intended to last no more than 10 years. Well, they’re still standing.

Lewes Today

Lewes still commands its prime position on the Delaware Bay, and much of its vibrant economy capitalizes on that location — outdoor activities, museums, retail and restaurants are popular with locals and visitors. The city is also the hub for a growing health care industry serving coastal Delaware. While it might be the state’s oldest city, it regularly ranks among Delaware’s top livable towns.

Don’t Miss in Lewes

Rehoboth Beach: The Nation’s Summer Capital

Fresh Air, Salt Water & God

In 1872, a group of Methodists bought 400 acres of land on the Delaware coast, which they called Rehoboth, a Biblical name interpreted as “broad place” or “having room for all.” Their purpose was to establish a summer camp meeting, i.e. a religious retreat, to help city dwellers renew their spiritual and physical health, a place where they could gather and pray — then take to the sea in heavy woolen bathing suits. Rehoboth was one of many leisure-by-the-sea retreats established in the late 1860s and ’70s as part of the wave of Methodist revivalism in America.

The Methodists quickly laid out the grounds in a fan-shaped pattern with streets wider the closer they were to the beach to pull in the cool Atlantic breezes. Lots sold for $50 each. Some of the faithful preferred old-style camping in white cotton tents around the tabernacle building. Others constructed “camp houses,” one-room cypress or pine structures with a front porch and sleeping loft.

Alas, the religious experiment proved short-lived. One of the Methodist founders put up a hotel and permitted card playing and drinking. When railroad service reached Rehoboth in 1884, things began to change quickly. Additional hotels, boarding houses and stores were built to accommodate the influx of secular tourists.

An official government was formed, and civic improvements such as sewer systems and streetlights were installed. Dancing, drinking and courting took place on the boardwalk. Artists came to paint among the pine trees, dunes and beaches. By all accounts, Rehoboth in the early 20th century was booming like other resort towns along the mid-Atlantic coast.

The Mosquito Matron

Rehoboth had one little problem. Actually, it was a big problem — mosquitoes and biting flies. Given the town’s location near coastal marshes and wetland forests, clouds of mosquitoes descended upon the town at sunset. Animals were driven to bellowing madness by the stinging insects. Homeowners screened their porches and covered their legs with newspapers while sitting on the beach to keep the flies away whenever a land breeze blew.

Enter Mrs. H.B. Thompson, a wealthy and politically connected summer resident and close friend of the DuPont family. The wife of a U.S. Senator, she detested bright lipstick on women and led the defeat of women’s suffrage in Delaware. That said, she helped establish the Rehoboth Art League and, in the 1930s, she organized a group of women to rid Rehoboth of its mosquito problem.

Consulting with experts from President Theodore Roosevelt’s administration who had experience with mosquitoes during the building of the Panama Canal, she brought valuable tactical advice to the battle, such as spraying massive doses of chemicals and kerosene and digging irrigation ditches. Largely through her efforts, Civilian Conservation Corps soldiers armed with shovels drained coastal marshes that served as mosquito breeding grounds. The efforts worked.

The Bay Bridge

Probably the biggest impact on Rehoboth’s history was the Chesapeake Bay Bridge opening in 1952. Residents of Washington, DC, had always vacationed in Rehoboth, the closest Atlantic beach to the nation’s capital, but now the trip became much quicker as the bridge replaced slow ferryboat service. So many DC residents, diplomats and government officials came to Rehoboth for their summer vacations that the town quickly became known as the nation’s summer capital, a moniker it retains today.

Richard Nixon vacationed in Rehoboth in the 1950s when he was a young senator. Some say he started working on his famous “Checkers” speech while staying with friends in Rehoboth. When first daughter Lynda Bird Johnson and her fiancé Marine Captain Chuck Robb (yep, the future senator from Virginia) partied on Rehoboth Beach in the summer of 1967, it made headlines across the nation. Washington insider and writer Sally Quinn was a young reporter for the Washington Star when she chronicled the social goings on in Rehoboth Beach in the late 1960s.

Rehoboth Today

Rehoboth Beach was founded as a summer resort, and for the most part it remains a traditional vacation getaway for families. Delaware’s most popular destination draws up to 50,000 visitors a day during the peak summer months. Its quaint sophistication has made it a favorite destination for mid-Atlantic gays and lesbians.